The European Business Review

By Quinn Bauriedel & Jeff Klein

Like the multitude of teams in any organization, theatre works under tight timeframes, combines many individuals with different talents, and communicates a vision of the world with the intent to attract and transform its constituents. Below, Quinn Bauriedel and Jeff Klein discuss Creating and Leading High Performing Teams, an open-enrollment program for organizational leaders.

Like the multitude of teams in any organization, theatre works under tight timeframes, combines many individuals with different talents, and communicates a vision of the world with the intent to attract and transform its constituents. Below, Quinn Bauriedel and Jeff Klein discuss Creating and Leading High Performing Teams, an open-enrollment program for organizational leaders.

Michael Kemmerer faced a familiar leadership challenge. A recognized expert, Michael was asked to assume leadership of a technical support team for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. His technical proficiency was exemplary and he had a mastery of the specialized knowledge necessary to provide quality support. Now he felt himself tested in another way as he was tasked to lead a team of his peers. He had done all the jobs that he was now leading and felt, as many would, that there was a right way to do it. His leadership style, at the time, was best described as “This is how I would have done it.”

His epiphany came in the form of a play he created as part of a newly-assembled team of managers. Looking back, he describes the shift in perspective that he gained through theatre – a realization that his leadership must encourage and support the contributions of his team. “Everyone can lead in his or her own right. We have knowledgeable folks that are experts and they can be leaders. There is not just one leader in the course of a day. There are many leaders,” said Kemmerer.

“The program exemplifies Pig Iron’s belief that we all work at our best when we are on the creative edge, not repeating the same task but achieving something new at a high level.”

The Pig Iron Theatre Company and the Wharton Leadership Program have collaborated to deliver leadership development training and education to hundreds of MBA students, managers, and executives over the past seven years. Of particular interest for this article, the authors have partnered to offer Creating and Leading High Performing Teams, an open-enrollment program for organizational leaders delivered at the Aresty Institute for Executive Education at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. While we are certainly not the first to incorporate experiential theatre exercises into leadership development programs, we do eagerly join the cadre of theatre professionals and leadership educators who have found the theatre to be so relevant and transferable to organizational contexts.1 Like the multitude of teams in any business or organization, theatre works under tight timeframes, requires the excellence and presence of many individuals with different talents, and communicates a unique vision of the world with the intent to attract and transform its constituents. Workshop participants conclude the day by highlighting the lessons of a rich theatre experience that can aid and support the organizational leader.

The Leading High Performance workshop delivered at Wharton by the Pig Iron Theatre Company draws upon the rich experiential traditions of Joe Chaikin (presence), David Kolb (experiential learning), Jacques Lecoq (physical theatre), Kenwyn Smith (group dynamics, power and authority), and Michael Useem (the leadership moment)2 3 featuring the essential components of action, reflection, and transference of learning to familiar organizational contexts. Creating and performing a new play represents a stretch experience4 for the team, as the participants are thrust into a new environment and asked to learn new skills while reaching high levels of performance as a team. The Wharton leadership development framework highlights the importance of stretch experiences, in particular, to meaningful and memorable personal leadership development5. These lessons and their applications to teams in a variety of organizational contexts are described below.

In this program, Pig Iron leads a 12 hour team performance training for an international group of executive education participants. Using the Leading High Performance framework, each team creates and performs an original piece of “Tony Award-caliber” theatre.

The task is defined at the outset of the day. In the next 12 hours, each team will develop, write, design, rehearse, and premiere an original 10-minute play that strives to win a Tony Award. The standard is extraordinarily high – perhaps unachievable! – so that focus and ambition never lag. Kemmerer, reflecting after the fact on his thoughts at the top of the day, said “there is no way a group of business people are going to be able to do this.” The program exemplifies Pig Iron’s belief that we all work at our best when we are on the creative edge, not repeating the same task but instead achieving something new at a high level. Clearly, leadership is most often built during extraordinary moments when leaders are outside their comfort zones, stretching their potential and learning experientially.

In their work in theatre, Pig Iron Theatre Company employs a flat rather than pyramidal organizational structure – a rarity in the traditional world of established theatre. Instead of starting with a script, giving the playwright full ownership of all the ideas and creating a context in which everyone else on the team merely interprets the playwright’s vision, Pig Iron artists encounter the material together. Having individuals with different expertise in the room – actors, director, designers, technicians, and writers – yields a generative performance from the efforts of all rather than the vision of one. This process recognizes the necessity of the team to solve an adaptive problem6 (a problem with no known or readily-available answer) – a challenge like creating an original piece of theatre, launching a new product, or acting on customer feedback.

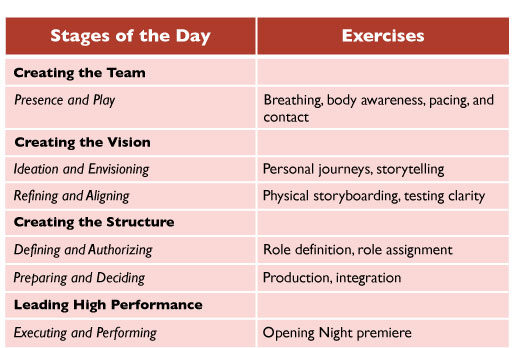

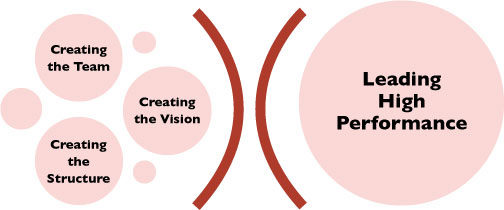

The Leading High Performance process moves through distinct phases which create the internal conditions described by J. Richard Hackman in Leading Teams:7 a real team, a compelling vision, and an enabling structure. The external conditions – a supportive organization and competent coaching – are provided through the weeklong Creating and Leading High Performing Teams program and the expert instructors from Pig Iron, respectively. The Leading High Performance process is described in detail below.

Creating the Team

As educators, the authors strive to create and support teams which will achieve the three criteria of the High Performing Teams test: Did we accomplish the goal? Did we learn and develop (individually and collectively) as a result? Would we do it again?8

Presence and Play

All leaders rely on presence, and we find presence to be as essential for team leaders as it is for artists and performers. Without presence, a team can become distracted, disengaged and unfocused. Successful team projects require the full presence and engagement of every member of the team, and the Leading High Performing process invests a few hours in establishing the concept of an engaged team committed to creating a collective product of high quality.

Plato famously commented that we can learn more about someone in an hour of play than in a year of conversation, and the Leading High Performance process uses playful and powerful theatre techniques to accelerate trust and engagement within the team. Through exercises introducing concepts such as presence, breathing, body awareness, and contact, the team finds the connections necessary to enable future work. Jesse Leon, an Account Director at Discovery Communications, Inc, commented about one such exercise, “The flocking exercise [where participants follow the movements of leaders who shift from leading the “flock” to following a new leader] showed how we create unison. The role of the leader and the role of the team evolves, and we start to mimic behavior and follow each other.” Leadership of the team, in theatre and in business, must smoothly transition from teammate to teammate as the skills and experience required by a dynamic environment also shift.

Creating the Vision

We seek a vision that is compelling and engages the team and the audience. Another colleague in the Wharton program, mountaineer and entrepreneur Chris Warner, has this to say about creating a vision: “It’s the leader’s job to create a compelling saga, otherwise those around him [or her] will fill it in with their own petty drama.”9 While the pun is certainly intended here, what is unique about this part of the process is that there is no designated leader, or director, in theatre parlance. Success in this model requires each team member to feel the responsibility for creating and sustaining a compelling vision.

Ideation and Envisioning

This crucial step in the process ensures that creative input comes from everyone. Before roles are assigned (or even revealed), the teams spend time sharing individual stories about journeys and significant events in their lives. Rather than starting with one leader’s master plan, this phase seeks wild ideas and seemingly impossible solutions and leads to collaboration because the vision arrives before roles are defined. Everyone is an owner of the project as all have submitted input.

Leon, summarizing an essential lesson from his recent participation, said, “When you let go, when you let the team work together… ideas start bubbling up, ideas I truly wasn’t coming up with. At the end of the day, our success was based on the ideas that came from the team, not just from me.” Too often in organizations, personal agendas trump team goals and vision. During this workshop, participants experience first-hand the benefit of creating a vision first – with active and equal contribution from the team – rather than becoming mired in the interdepartmental politics that can bog down any cross-functional team.

Refining and Aligning

Before preparation and production can begin, the ideas generated during the ideation phase must be tested. The vision must be “put on its feet” in front of an audience. The audience then provides direct and immediate feedback, much like a new product focus group, that enables the team to refine its performance for maximum impact.

Astera Primanto Bhakti, Director of the Centre for State Revenue Policy in the Indonesian Ministry of Finance, highlights the impact of creating a compelling vision. “Team alignment,” said Bhakti, “around the vision and main objectives is crucial, both for my team in the Pig Iron workshop and my daily work.” Bhakti has brought this lesson into his community partnership efforts, using direct feedback from community members to refine government programs and reinforce key success metrics.

Creating the Structure

We particularly appreciate Hackman’s notion of an “enabling structure” within high performing teams. An enabling structure is more than an organizational chart and a set of job descriptions – it also emphasizes key milestones, productive team norms, and the interdependence of individual roles. In practice, the enabling structure includes a detailed and fast-paced production timeline and the sets of decisions that each team member must make and understand. Roles are defined and assigned, including writers, designers, actors, and a director (the designated leader). Through the work of making specific choices and integrating these decisions into the final production, the team confronts common organizational challenges – coordination and collaboration, boundary management, communication, and adaptation to environmental changes.

“Before preparation and production can begin, the ideas generated during the ideation phase must be tested. The audience then provides direct and immediate feedback, much like a new product focus group, that enables the team to refine its performance for maximum impact.”

Defining and Authorizing

Once the vision has been established and the team is committed to the project’s direction, roles – including writers, designers, actors, and a director – are distributed. The roles have clear guidelines and every team member will make important decisions and integrate these choices into the final product. The director is the designated leader of the team, though the designated leader in the Leading High Performance process is most typically experienced as a guide toward a clearly defined end-point, selected by the team to make the team shine brightly.

Leon described the ease with which roles were distributed: “I was surprised to see – with such strong leadership in the team – the ability of those strong leaders to step back and take on the tasks they were asked to do. The greater good of the team became quite clear and everyone got on board quite quickly.” Stated simply, teammates take up their assigned roles fully, savoring the opportunity to be a part of something bigger than themselves.

Preparing and Deciding

The success of the play – or any project – depends on attention to detail and precise, well-timed decisions. Once the vision has been set, all on the team, in their various roles, must contribute to the goal of producing a play that evening. The team must work efficiently and collaboratively, and take up their authority to create the best possible outcome.

Bhatki, reflecting on this part of the day, commented, “First of all, this part is very exciting for me – using theatre for leadership training. I learned a lot about how to manage people and how to deal with strict and limited time to achieve a goal.” He highlights the quick decisions made by each team member to translate the vision into an actual performance as a lasting memory of the program.

Leading High Performance

Trust and alignment must be created before a team performs, whether the team is a theatre company or a cross-functional product development group. At this stage – the moments before and during performance – Pig Iron takes the team back to its initial level of engagement, vulnerability, and connection at the beginning of the day. With a real team, an aligned vision, and an enabling structure (located in a supportive culture with easily accessible expert coaching), the teams debut their original theatrical productions.

“All high performing teams – executive teams, sales teams, artistic teams, product development teams – recognize the importance of vision. When teams succeed, however, it is the result of everyone working toward a clear vision.”

Executing and Performing

The conclusion of this experiential learning module is a performance that has been created from scratch during the course of the 12-hour day. Before their performances, the teams are reminded to breathe, to be present, to listen, to support their team and, once again, to share the team’s vision with an audience. That one second of team connection before executing can make a world of difference.

The performances highlight stories and themes that are quite compelling, and capture the moments of joy, sorrow, achievement, and loss that run through all of our lives. Perhaps the best testament to the quality of the experience comes from Kemmerer, who said, two years after completing the program, “I don’t remember what I did last week but I remember the plays.”

In Closing

All high performing teams – executive teams, sales teams, artistic teams, product development teams – recognize the importance of vision. Too often, individual goals and team goals are out of alignment with individuals sometimes seeking personal gain at the expense of the team’s success. When teams succeed, however, it is the result of everyone working toward a clear vision. We find that when a group of individuals comes together to form a team, their success is often the result of everyone believing in the vision, a vision that is bigger than any individual. Michael Kemmerer learned, through the Pig Iron – Wharton collaboration, that success will come not from him playing all the parts on his team but from the seamless orchestration of many individuals all working toward one goal. Theatre is a discipline that does not happen through one person’s efforts. A play that is written, directed, performed, designed, produced, stage-managed, house managed and marketed by one person does not exist. Successful, Tony Award winning theatre, therefore, is the result of a grand and compelling vision, real collaboration from everyone involved, integrated thinking, and a sense that everyone is a vital contributor to the whole. If we demand this from our theatre, why not demand it from our business teams?

Download the digital edition of The European Business Review from Zinio.

About the Authors

Quinn Bauriedel is a Founder and Co-artistic director of the OBIE Award-winning Pig Iron Theatre Company. He teaches The Leader As Storyteller, Leadership Presence, and Leading High Performance to executives and MBA students through the Wharton School and to leading businesses and organizations. Quinn is the recipient of a Pew Fellowship, a Luce Fellowship (sponsoring a year of study in Indonesia), a Fox Fellowship and was one of 50 American artists in 2010 to be named a USA Knight Fellow. He regularly teaches at Princeton University and Swarthmore College and leads workshops throughout the U.S. and abroad. He can be reached at Quinn@pigiron.org. http://www.pigiron.org/

Jeff Klein is the Executive Director of the Wharton Leadership Program and a Lecturer at The Wharton School and the School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. He is responsible for the portfolio of leadership development programs available to Wharton undergraduates, full-time MBAs, and executive MBAs. His research and teaching focuses on collaboration within and across boundaries, and he designs and delivers leadership workshops and courses for executive clients through Wharton Executive Education. As a Learning Director, Jeff leads two weeklong executive courses, Creating and Leading High Performing Teams and The Leadership Edge. He can be reached at kleinja@wharton.upenn.edu. https://leadershipcenter.wharton.upenn.edu

References

- See, for example, Posner, B (2008). “The Play’s the Thing: Reflections on Leadership from the Theatre,” Journal of Management Inquiry, 17: 35-41, and Gagnon, S., et al (2012). “Learning to Lead, Unscripted: Developing Affiliative Leadership Through Improvisational Theatre,” Human Resource Development Review, 11: 299-325.

- For more information on experiential leadership development, we refer you to Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (Kolb); Groups in Conflict: Prisons in Disguise (Smith); and The Leadership Moment (Useem).

- For more information on the educational traditions of the theatre, we refer you to The Presence of the Actor (Chaikin) and The Moving Body: Teaching Creative Theatre (Lecoq).

- Klein, J (2012). “Leadership Development and the High Performing Team: The Wharton Leadership Program,” The European Business Review, September-October 2012, 40-42.

- Useem, M (2012). “The Leader’s Checklist,” The European Business Review, January-February 2012, 7-10.

- Heifetz, R (1994). Leadership Without Easy Answers. Harvard University Press.

- Hackman, J (2002). Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances, Harvard Business School Press.

- The High Performing Teams test is described in more detail in: Klein, J (2012). “Leadership Development and the High Performing Team: The Wharton Leadership Program,” The European Business Review, September-October 2012, 40-42, with acknowledgment to J. Richard Hackman and Rodrigo Jordan.

- See Warner, C (2008). High Altitude Leadership: What the World’s Most Forbidding Peaks Teach Us About Success. Jossey-Bass Press.