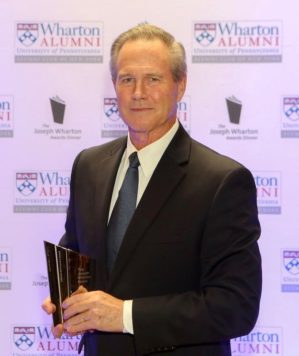

Professor Mike Useem sat down in October 2018 with Arthur D. Collins, Jr., former chairman & CEO of Medtronic and the 2018 Joseph Wharton Lifetime Achievement Award recipient, to discuss why many military officers have gone on to be successful business executives. Mr. Collins was an officer in the U. S. Navy and served aboard the destroyer USS Vogelgesang before receiving his MBA degree from the Wharton School. He is a current board member of Arconic, Boeing and US Bancorp, and past director of Alcoa, Cargill and Tennant. Mr. Collins was a consultant at Booz, Allen & Hamilton and an executive at Abbott Laboratories before serving as Medtronic’s president & COO and chairman & CEO for over 15 years. He also presently serves as a senior advisor at Oak Hill Capital Partners in addition to being a managing partner of Acorn Advisors, LLC.

Professor Mike Useem sat down in October 2018 with Arthur D. Collins, Jr., former chairman & CEO of Medtronic and the 2018 Joseph Wharton Lifetime Achievement Award recipient, to discuss why many military officers have gone on to be successful business executives. Mr. Collins was an officer in the U. S. Navy and served aboard the destroyer USS Vogelgesang before receiving his MBA degree from the Wharton School. He is a current board member of Arconic, Boeing and US Bancorp, and past director of Alcoa, Cargill and Tennant. Mr. Collins was a consultant at Booz, Allen & Hamilton and an executive at Abbott Laboratories before serving as Medtronic’s president & COO and chairman & CEO for over 15 years. He also presently serves as a senior advisor at Oak Hill Capital Partners in addition to being a managing partner of Acorn Advisors, LLC.

Useem: A number of former military officers have subsequently turned out to be very capable CEOs—for example, Alex Gorsky at Johnson & Johnson, Richard Kinder at Kinder Morgan, Clay Jones at Rockwell Collins, Kevin Sharer at Amgen, and Fred Smith at FedEx, just to name a few. Since you served as an officer in the United States Navy and then went on to successfully run Medtronic as chairman & CEO, what was the most important aspect of leadership you learned in the military that prepared you for your career in business?

Collins: From that early morning in August of 1969 when I reported to Naval Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island as a wet-behind-the-ears 22-year-old college graduate, to the day over four years later when I was honorably discharged from military service as a full lieutenant, I learned a great deal about leadership. I also made my share of mistakes along the way. Even though there are many nuances to effective leadership, it has been my experience that all great leaders display one endearing trait: integrity. As General Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “The supreme quality for leadership is unquestionable integrity. Without it, no real success is possible.” Great leaders understand this critical tenet, as well as the importance of character, courage, and leading by example.

Useem: What other leadership traits did you learn and how did you learn them?

Collins: Some of the leadership skills came to me the hard way through personal trial and error. I also learned from observing the actions of respected and not-so-respected officers, and many of those observations were reinforced through reading about many of the great leaders in the past. So, with that as a backdrop, let’s start with honesty. Telling the truth is a basic cornerstone of integrity. As a new officer candidate, I learned that the appropriate response to any question for which I didn’t know the answer was never to wing it, but to answer, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out.” I also knew that if I failed to tell the truth as an officer, I would be immediately relieved of duty. Even though honesty is currently not a hallmark at some of the most senior levels in our government, its importance cannot be underestimated in gaining the respect and allegiance required to lead. It’s been my experience that dishonest leaders may survive for a while, but they are doomed to ultimately fail.

Useem: Military officers are expected to carry out orders. How does that figure into leadership?

Collins: You’re right. All military officers take a solemn oath of loyalty to support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic, and to bear true allegiance to the country. While officers understand the importance of following orders, their allegiance is first and foremost to country and not to any one person. I learned early on that leaders who demand blind loyalty and who put their own personal interests ahead of the best interests of the organizations they represent have their priorities backward. A Machiavellian leader of this type also is ultimately doomed to failure. It is interesting to note that Richard Nixon, the president and commander in chief during the time I served in the military, demanded personal loyalty above all else, and he finally resigned in 1974 rather than face impeachment.

Useem: Much has been written about leaders being both responsible and accountable. How did that concept play out when you were an officer?

Collins: Being “present and accounted for” and fulfilling one’s responsibilities is expected of every officer; to do otherwise would constitute a dereliction of duty. Every officer also understands that it’s not enough to simply show up. A leader needs to be present and to act in a consistent and ethical manner, not just some of the time, but all of the time. In addition, a good leader should be a good follower whenever that is required. Along these lines, I was taught that an essential part of leading by example is never asking those in your command to do something that you weren’t prepared to do. General Colin Powell had it right when he said, “The most important thing I learned is that soldiers watch what their leaders do. You can give them classes and lecture them forever, but it is your personal example they will follow.”

Useem: You said that you were in your early 20s when you assumed your first command. What did you learn right off the bat?

Collins: As a newly commissioned Ensign, I was assigned to a destroyer with responsibility for the Antisubmarine Warfare Division of about twenty men, ranging in ages from 19 to 50. It immediately became clear to me that in order to do my job, I needed to earn respect, and I underscore the word “earn,” and then rely on my Chief Warrant Officer, my Chief Petty Officer, and all the other enlisted men under my command. Each member of the team had a job to do, and I recognized that we were only as strong as our weakest link. Whether in the Navy or later in my business career, I found time and again that whenever I assembled a team, the better and more motivated they were, the easier my job became.

Useem: We hear a lot about military training and combat exercises. What was that like?

Collins: While good leaders need to be nimble and able to react as events unfold, I learned that nothing improves the odds of successful execution more than effective planning and training, including the development of contingency plans for what might go wrong. In addition to my assignment as the destroyer’s ASW Officer with responsibility for launching conventional and nuclear torpedoes, I served as the ship’s Gunnery Liaison Officer. Stationed in the ship’s Combat Information Center, it was my job to provide coordinates when the ship’s three twin 5” guns were fired. Considering the dire consequences if mistakes were made, long hours of repetitive training were required. That arduous training ultimately paid huge dividends when live combat exercises were carried out. As a young officer, I also recognized that an important part of being prepared is learning from previous mistakes. Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the “Father of the Nuclear Navy” and a living legend during my time in the military, once said, “It is necessary for us to learn from others’ mistakes. You will not live long enough to make them all yourself.”

Useem: Former presidential speechwriter James Humes said, “The art of communication is the language of leadership.” What did the Navy teach you about communication?

Collins: To be perfectly honest, public speaking used to scare me to death while I was growing up, and I initially wasn’t very good at it. During college and later in the Navy, I recognized that if I couldn’t communicate effectively, both orally and in writing, my ability to lead would be significantly hindered. During my OCS training, I heard repeatedly that an officer was expected to communicate clearly so orders were understood; confidently so those following orders would believe in the wisdom of what was being asked; and passionately so others would find the emotion and inspiration to achieve their best. I also learned the importance of the sometimes-lost art of communication—listening. And going back to my previous comments, I came to realize that practice and preparedness certainly increased the probability of effective communication.

Useem: Good leaders need to act decisively. You said before that you learned a lot through trial and error. Can you give us a real-life example in this regard?

Collins: You’re right about decisiveness. Successful leaders don’t always make decisions before they are required to, but they always act decisively when they need to. I learned an important lesson in this regard during a deployment in the Mediterranean. It was a few minutes after midnight and I had just relieved the previous officer of the deck and had assumed the “con” on the bridge of the destroyer. We were participating in a dangerous nighttime exercise with an aircraft carrier group, and our assignment was to take the role of an enemy ship and to try to penetrate the shield of other destroyers and simulate an attack on the carrier. We were cruising at about 20 knots in silent mode without the radar or sonar activated, and visibility was very poor since there was little moonlight that night. I suddenly was terrified to see the carrier appear out of the darkness about 45 degrees off the port bow, heading directly into the vector of our current course—this is referred to as being in “extremis” in naval parlance. Previous training instinctively overcame fear and I immediately shouted out the commands, “Left full rudder. Port engine back full. Starboard engine ahead full.” Our bow slowly started to drift to the left moments later, and then the port turn began to pick up momentum, finally passing by the starboard stern of the carrier with about 150 yards to spare, which was well inside the margin of safety. After a collision at sea had been averted and my heartbeat returned to normal, I had time to reflect on benefits of being present, being prepared, and acting decisively to avert a calamity—as would be the case many more times in my future.

Useem: Were you always on call when you were aboard the destroyer?

Collins: With the exception of the limited days I spent on leave, the time I served in the Navy was on a 24/7 basis. Work days were long and the formal watches I stood continually rotated, starting and stopping at various times during the day and night. I often was operating with little sleep and under significant pressure, and there usually was little margin for error. From the moment I entered the Newport Naval Base, slacking off or giving up was not an option. You learned to do what was required and not complain, particularly as an officer who was constantly being watched by the sailors in your command. While many would argue that drive and perseverance are innate qualities, these attributes certainly were honed while I was in the Navy and that experience definitely helped prepare me for many of challenges I faced in civilian life and in business during the years that followed.

Useem: Along those lines, we hear a lot about the pressure and long hours that come with being a CEO. How did the Navy prepare you for those mental and physical challenges?

Collins: As a student-athlete, I always had been told that physical and mental fitness go hand in hand. That theory was put into practice and to the test during the four months I spent in OCS training. Reveille was at 05:00 each morning. Since a surprise barracks inspection could immediately follow, most officer candidates slept under their blankets on already-made beds. Once up, nonstop calisthenics commenced in the hallway and lasted for about 30 minutes. After the morning meal, officer candidates gathered by company and marched to their first academic class. Classes concluded before dinner, and then it was back to the barracks for study until lights out at 22:00. While life aboard the destroyer was not as regimented as at OCS, I continued with my calisthenics routine just as I now do every morning. I am convinced that my ability to endure the stressful life of travel and pressure that came with being a senior executive and ultimately the chairman & CEO of a multinational corporation was made easier by the skills and practices I adopted while at OCS and later as an officer.

Useem: Are there any other significant lessons you learned while serving as a Naval officer.

Collins: Military service is serious business. Lives often hang in the balance and the safety of our nation sometimes is at stake. Recognizing this, an additional valuable lesson I learned was that while I should always take what I was doing very seriously, I should never take myself too seriously. On land and at sea I witnessed firsthand the benefits of maintaining balance in one’s life and the importance of occasionally taking a little time off to have fun and build comradery. No one can work effectively, let alone lead, if they are burned out. While I learned that judgment can become impaired if the work/life equation gets severely out of balance, I also came to recognize that individual tolerance for hard work and pressure varies widely—in other words, what is over the “red line” for one person may be just what another person requires in order to excel. Finally, I came to appreciate leaders who are able to maintain their composure and keep a good sense of humor in the worst of times.

Useem: Art, this has been very helpful. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Collins: While I wouldn’t trade my service in the Navy for an equal amount of time spent doing anything else at that time in my life, I don’t want to imply that serving as a military officer guarantees success as a leader. It would be an understatement to say that there have been many great leaders who never served in the military, and it is just as true that there have been many military officers who turned out to be inept leaders. Finally, I have come to believe that there is no single mold, personality, or physical characteristic that defines a successful leader—in the military, government, business, or any other walk of life. If you need proof of that, compare Winston Churchill and Mahatma Gandhi. With that said, I believe that many of the traits and lessons we’ve just discussed can help anyone aspiring to a leadership position.

Mike Useem is the William and Jacalyn Egan Professor of Management at the Wharton School and the Director for the Center for Leadership and Changement Management. His university teaching includes MBA and executive-MBA courses on management and leadership, and he offers programs on leadership and governance for managers in the United States, Asia, Europe, and Latin America. He the author of a multitude of books including the Leader’s Checklist, the Leadership Moment, and the Go Point.

Art Collins retired from Medtronic in 2008 after serving as the corporation’s chairman & CEO and president & COO for over 15 years. Medtronic is the world’s largest medical technology company with annual revenues of $30 billion and 98,000 employees in over 160 countries. Art joined Medtronic from Abbott Laboratories where he was corporate vice president with responsibility for Abbott’s worldwide diagnostic business units.